“If you think you’re too small to have an impact, try going to bed with a mosquito.” ANITA RODDICK

Ladies and gentlemen… your attention please.

© www.123rf.com/profile_karapas

Impact, Charisma and Presence are essential qualities in a Senior Executive. If a leader wants to influence peers, enthuse employees, inspire confidence in regulators and officials it is vital that they express themselves fully and with a sense of conviction. Presence, then, is a key attribute that effective leaders possess; one that enables them to motivate others. The dictionary defines ‘Presence’ as…

- The state of being closely focused on the here and now, not distracted by irrelevant thoughts

- A quality of poise that enables a person to achieve a close relationship with an audience

So Impact and Presence is about paying full attention to, and connecting with, the feelings of other people in order to inspire them to take a given action. And once you’ve got a ‘connection’ it’s about voicing an opinion, that’s based on logic and analysis, in a clear, concise, and compelling manner.

And, as with so many other qualities, it is a skill that can be learned.

Learning from the past

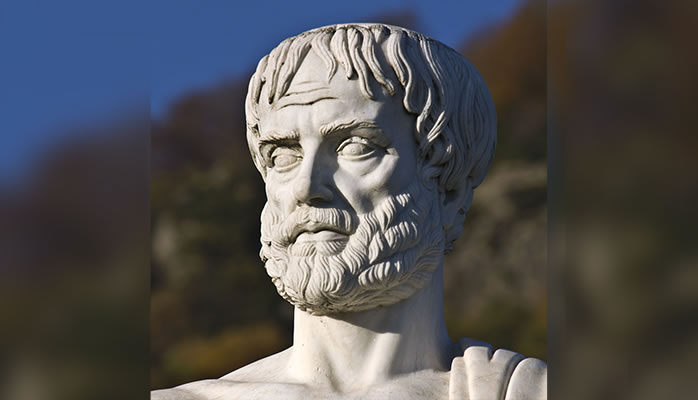

Research into leadership qualities has a long history. The ancient Greeks highly valued public speaking and over 2,000 years ago Aristotle identified “the three persuasive appeals” that combine together to make a powerful argument that inspires people to act. They are:

- Ethos: being credible as a speaker

(e.g. being thought of as trustworthy and knowledgeable) - Pathos: building emotional connection to the audience through establishing common ground or linking to key values

- Logos: having logical argument supported by data, facts and analysis

Much of what is taught today in respect of presence goes back to these writings on rhetoric (or the art of persuasion) by the ancient Greeks.

For example, in their June 2012 HBR article Antonkis, Fenley and Leichti on Learning Charisma, note that while leaders can pressure people to do as they ask because they have the power to reward or punish employees, it is the ability to demonstrate charismatic leadership that really inspires people to give of their best. They go on to highlight twelve ancient rhetorical techniques as being especially powerful for modern leaders. These include…

Rhetorical Questions to engage people e.g. “So, what does good performance look like?”

Expressing Moral Conviction (setting standards for right or just behaviour) e.g. “This quality problem is damaging our relationships with our customers, it’s our issue to resolve and we need to take ownership for fixing it as a group.”

Reflecting the Group’s/Audience’s Sentiments – even when they are negative – as they show empathy and help the group to ‘connect’ with the speaker e.g. “I know how disappointed and upset you are about this decision… it is a bitter pill to swallow after all your hard work…”

Setting Challenging Goals – giving people a clear, compelling objective to focus on e.g. “this Nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon”, John. F. Kennedy (May 1961).

Learning from the present

Moving on to the 21st century recent research at Cambridge University (‘Social Networks and Leader Charisma’) demonstrates that leaders who are regarded as charismatic by their teams will have a high-performing group. So, impact and presence does affect team performance. They also note that being charismatic in this context is primarily about; “becoming an expert (i.e. ‘ethos’) plus soliciting advice from people, and treating people with consideration” (i.e. pathos), highlighting that both ethos and pathos are vital components of developing great teams.

A study published in the Journal of Behavioural studies (September 2014) analysed the attributes of a cross section of Charismatic Leaders (all US based) and identified the following attributes associated with making an impact…

- Being Genuine: talking from the heart, being sincere and honest (and consistent)

- Meeting Expectations: dressing appropriately, looking fit and heathy

- Working the room: connecting with audience or group members before the formal talk/meeting starts. This involves shaking hands with people, making small talk, picking up on the mood of the group etc.

- Reading the Room: observing people’s reactions to what’s being said during the actual meeting or talk and adjusting behaviour accordingly, in ‘real time’

- Using humour to connect with an audience

- Storytelling

Storytelling was seen as particularly important as it made messages memorable and easy to digest. Also, stories that involve (or relate to) members of the group are a powerful way of forging a connection between the leader and the team.

Getting the body language right – Communicate like Clinton?

Positive body language is a key aspect of demonstrating charisma; especially adopting an upright, relaxed posture, coupled with steady eye contact and a warm smile.

Michael Ellsberg, author of The Power of Eye Contact argues that exuding presence has a lot to do with the number of behaviours a person employs when communicating their message. So ex US President Bill Clinton, for example, when meeting someone makes eye contact and smiles and touches their hand or upper arm and raises his voice slightly, to communicate his message in a powerful way.

A voice of your own?

Part of having presence is to be able to use your voice to communicate emotion to the listener and so motivate them to action e.g. by signalling things like urgency, seriousness, happiness, surprise, caution (and sometimes anger). Also, to use voice energy to capture their attention by varying the volume from a stage whisper, to a clear, controlled statement of the facts and on to a commanding call for action!

Patsy Rodenburg (the world-renowned acting coach) emphasises the power of a strong voice, breathing exercises and mental focus to project energy and connect with people. In her book, The Second Circle: How to Use Positive Energy for Success in Every Situation, she explains how to find and release tensions and project your voice to engage with the listener.

Leadership presence – acting the part

In their book Leadership Presence Halpern and Lubar (like Rodenburg) make a link between what is required of a top performing senior executive and the actor’s craft. They note that actors don’t expect to be ‘born’ with charisma but train, using specific ‘drills’, to be able to capture an audience’s attention and to have people focus completely on them.

Of course leaders have many skills that actors don’t e.g. they understand corporate strategy and markets and can negotiate effectively but the need to ‘connect’ with others is a common thread between the two worlds. For example they argue that the only way to elicit emotion and/or a given level of energy from a work group is to actually express that level of emotion or energy personally. They suggest using a technique known as ‘emotional memory’ to be able to project emotions in an appropriate and positive way.

Also, a good performance based on a poor script doesn’t impress anyone: presence captures people’s attention and gets them to take the speaker seriously, but the content of the message must also be compelling. So effective leaders don’t only make their point with energy and conviction (pathos), they also have something to say that is worth listening to (logos).

Six key lessons about Presence

Looking at the research we can highlight six fundamental aspects of developing a strong presence:

- Stand up straight, make eye contact and smile (a genuine smile).

- Put energy into your voice and breathe fully.

- Be interested in other people and what they have to say to you.

- Develop a logical proposition or argument to put forward (and script and rehearse what you want to say).

- Make what you say relevant to the other person’s situation. (How are you helping to ‘solve their problem or address their issues?’)

- Pay attention to the other person’s body language and adjust what you are doing in the light of how you see them reacting.

So what’s next?

Reflect on how much you really listen to other people when you talk with them. Make a determined effort to give them your undivided attention.

Consider what your body language says about you. What messages are you (unconsciously) transmitting through your posture or your use of gestures? Focus on ‘standing upright’ and relaxing your body as you talk with people.

Reading

Try reading, The Power of Presence unlock your potential to influence and engage others by Kristi Hedges (AMACOM, 2011)

On-line

Have a look at this YouTube clip (15 minutes) on Making A Positive First Impression by Olivia Fox Cabane, author of the Charisma Myth

www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zRZ5j2O07w

Courses

Take a look at our intensive two day in-house programme on Impact and Presence (an intensive training course for a maximum of six delegates per programme)

Coaching

Or maybe review our ‘One to One’ executive coaching services to get some personal guidance on developing your personal impact.

Article

Download this article as a pdf

Contact

Give us a call on 0844 394 8877 (UK) or +44 1788 475 877 (international) or email us at coaching@boulden.net and we’ll be happy to discuss how we can work with you.

And we end with a quote about the well-known Shakespearean characters in Julius Caesar…

“When Brutus spoke the crowd cheered; but when Antony spoke they marched.”